Mental Model

May 26, 2025

30

Min

A Comprehensive Guide to Mental Models

No items found.

Your mind is a kind of mental toolbox. Mental models are simply the tools inside it – they are established concepts, frameworks, or ways of looking at the world that help you understand how things work. They're like blueprints for thinking. The more tools you have in your toolbox, and the better you know how and when to use each one – a wrench for this, a level for that, a detailed schematic for complex projects – the more effectively you can tackle any challenge that comes your way. Without them, we often default to just a couple of familiar "go-to" tools, whether they're the right fit for the problem or not.

Now, why should this matter to you? For Priya, learning to use different mental models wasn't just an interesting intellectual exercise. It fundamentally changed how she approached her business. Suddenly, complex decisions became clearer. She could anticipate challenges further down the road, not just react to immediate fires. She found she could solve problems more creatively and efficiently. And here’s the really exciting part: these kinds of results aren't unique to Priya. By consciously building up your own toolkit of mental models, you can:

It might sound like a big undertaking, but like any skill, it starts with learning the first few tools. This guide is designed to walk you through some of the most effective mental models out there, show you how they work in simple terms, and help you start applying them right away. Ready to upgrade your thinking? Let's begin.

Have you ever hit a wall while solving a problem that just wouldn’t budge - no matter how many times you rehashed your approach??

There was a client once struggling with reducing manufacturing costs for a new product line. Their default move? Benchmark against peers. But benchmarking can be a trap. You only end up iterating on what's already been done. What eventually helped them leap forward wasn’t more data - it was a change in thinking.

That shift came through First Principles Thinking.

Let’s unpack this together.

First Principles Thinking isn’t new. Aristotle spoke about it. Physicists use it. And yes, Elon Musk made it famous in business circles.

At its core, it’s about stripping a problem down to its bare essentials - the truths that are indisputable. From there, you build up a solution as if you’re solving it for the very first time, ignoring what’s always been done.

Musk explained it best when asked why batteries were so expensive: instead of accepting market prices, he asked, “What are the raw materials? What do they really cost?” That simple reframing led to cheaper, scalable battery packs for Tesla.

This is the power of First Principles Thinking - it frees you from conventional constraints and opens the door to original solutions.

We often think by analogy. That means borrowing from what’s been done before:

Analogy Thinking:

“All premium apps charge per user, so we’ll do the same.”

But First Principles Thinking flips the script:

First Principles Thinking:

“Why do apps charge per user? What are our actual costs per usage type? Could we charge by value delivered instead?”

Here’s what happens when you shift from analogy to fundamentals:

Applying First Principles Thinking doesn't require genius. It requires discipline. Here’s a practical process:

Precision matters. Get specific.

Try this:

Write the problem as a question:

“How might we reduce onboarding time for new hires by 50% without sacrificing training quality?”

Break it down like an engineer dismantling a machine.

Let’s say the problem is reducing building costs. You might ask:

This helps distinguish the must-haves from the assumed-to-haves.

Ask why, five times if needed. Push past norms.

Example:

This step is uncomfortable. Good. That means you’re getting somewhere.

Start assembling possibilities using only the truths uncovered in Step 2.

Ask:

This is where innovation takes root. This is where “we’ve always done it this way” finally loses its grip.

Rather than accepting that rockets are expensive, Musk asked:

“What are the raw materials in a rocket, and what do they actually cost?”

His answer: The parts cost far less than the final product. So he built from scratch.

Instead of “Save more this year,” break it down:

This simple reframe often reveals where meaningful cuts (or investments) can be made.

And perhaps most critically: it cultivates clarity. Leaders today don’t just need more answers - they need better questions. First Principles Thinking sharpens both.

In a world obsessed with best practices and competitor checklists, First Principles Thinking pulls us back to what matters: truth, clarity, and creativity. It reminds us that leadership isn’t about doing more - it’s about thinking better.

So, the next time you’re tempted to “see what others are doing,” pause.

Ask instead:

What do I know to be /absolutely true?

And build from there.

Try this today: Pick one decision on your plate. Break it down using Step 2 of this framework. Go deeper than what’s comfortable.

You might just find your breakthrough.

Have you ever solved a problem, only to discover that the solution created three new ones?

You’re not alone. It’s a familiar pattern in decision-making – we act, we fix, we move on. But sometimes, what we fix comes undone. Or worse, it pushes the problem further down the road.

That’s where second-order thinking comes in. A powerful mental model, it urges us to pause, reflect, and ask: “And then what?”

Let’s explore how moving beyond immediate consequences can lead to wiser, longer-lasting decisions.

First-order thinking is seductive. It's fast, it feels satisfying, and it solves something now. But as we’ve seen in everything from quick-fix diets to corporate cost cuts, what looks like a solution today can create ripple effects tomorrow.

The real thinkers – leaders, strategists, and changemakers – aren’t just solving today’s problems. They’re building tomorrow’s realities.

In this blog, let’s unpack the difference between first-order and second-order thinking and learn how to use this powerful lens in business, policy, and personal life.

This is reactive thinking. It focuses on the most obvious and immediate result of a decision.

Example: “Sales are down – let’s lower prices.”

It may feel logical, but it doesn’t ask deeper questions like: Will this attract the right customers? What happens to profit margins? How will competitors respond?

This is layered thinking. It explores not just the immediate effects, but also the consequences of those consequences.

Using the same example: “If we lower prices, will that start a price war? Will we attract bargain hunters instead of loyal customers? Will our brand get diluted?”

Second-order thinking doesn’t eliminate risk – it just makes us more conscious of it.

Good intentions don’t always lead to good outcomes. But thoughtful analysis often does.

Let’s break it down:

First-order: “Let’s slash prices to boost sales.”

Second-order: “Will this reduce perceived value? Will competitors retaliate? Will our operations handle increased volume?”

First-order: “Let’s cap ride-sharing prices to protect customers.”

Second-order: “Will fewer drivers be available? Will service quality drop? Will it reduce supply when demand peaks?”

First-order: “I’ll take this higher-paying job.”

Second-order: “Will it compromise my time with family? Will it lead to burnout?”

These layers are what distinguish reaction from strategy.

Sometimes, the danger isn’t in what we do – it’s in what we didn’t think through.

What’s quick and convenient now may snowball into complexity. Many policies, tech rollouts, or even parenting decisions falter here.

When we only look at the immediate path, we often miss the long tail of value – better alternatives that take longer to show up.

Many corporate decisions fail here. Layoffs that save cash instantly, but crush morale. Efficiency drives that kill creativity.

Remember: The problem with easy answers is they often breed harder questions.

What do we gain when we develop this mindset?

You anticipate roadblocks. You plan for contingencies. Your decisions hold up longer.

You don’t just treat symptoms; you address root causes.

You can't predict every outcome, but you can prepare for possibilities.

It’s the mental equivalent of strength training – slow at first, but incredibly rewarding over time.

Don’t stop at the first answer. Go 2–3 layers deep.

Ask: “What could go wrong?” “What would that trigger?”

Not just the best-case or worst-case. Try: “What else might happen that I’m not seeing?”

If I change X, how will it affect Y and Z?

Who are the stakeholders? What incentives are at play?

Reflect on past decisions: What did you miss? What surprised you?

You don’t need to have all the answers – you just need to ask better questions.

If there’s one thing second-order thinking teaches us, it’s this:

Shortcuts can cost more than we think.

We live in a world of urgency. But wisdom rarely shows up at full speed. It emerges when we pause, widen the lens, and think again.

Let’s summarize:

This week, try this:

Before making a decision, ask “What happens next? And then?” Map it out. Even 5 minutes of pause can reveal long-term costs or unexpected opportunities.

"The quality of your thinking determines the quality of your decisions."

As a business leader or entrepreneur, you face countless decisions daily – from the routine to the potentially transformative. Your competitive advantage? It's not just experience or resources – it's how effectively you think. Mental models – powerful frameworks that shape perception and guide reasoning – can dramatically improve your decision-making quality and business outcomes.

This guide explores 10 essential mental models that will elevate your strategic thinking, enhance your leadership capabilities, and sharpen your entrepreneurial instincts.

The most successful leaders aren't necessarily those with the most experience or resources – they're often those who think better. Every business challenge, whether allocating capital, building teams, or launching products, is directly influenced by the quality of your mental processing.

Mental models serve as cognitive tools that help you:

Consider mental models as your decision navigation system – providing reliable orientation regardless of the business terrain you're traversing.

The Framework: This classic model creates a comprehensive situational assessment by examining:

Practical Application: Before your next strategic planning session, have each team member independently complete a SWOT analysis. Compare the results to identify perception gaps and alignment opportunities. This exercise often reveals blind spots and generates valuable strategic insights.

Real-World Example: Netflix's successful pivot from DVD rentals to streaming demonstrated exceptional SWOT awareness – recognizing their strength in content delivery, the opportunity in emerging technology, the weakness of physical distribution costs, and the threat of emerging digital competitors.

The Framework: This model evaluates competitive intensity and market attractiveness through five dimensions:

Practical Application: Use this framework when entering new markets or re-evaluating your position in existing ones. It reveals structural forces that determine long-term profitability potential beyond current competition.

Real-World Example: Apple's ecosystem strategy directly counters all five forces – creating switching costs to reduce buyer power, controlling app distribution to limit supplier power, creating unique experiences to minimize substitution threats, and building technology barriers against new entrants.

The Framework: This principle states that roughly 80% of effects come from 20% of causes. In business contexts:

Practical Application: Conduct an 80/20 analysis of your customer base, product portfolio, or daily activities. Identify and double down on the vital few inputs generating disproportionate outputs.

Real-World Example: Microsoft famously discovered that fixing the top 20% of reported bugs would resolve 80% of system crashes and errors – allowing more efficient resource allocation in software development.

The Framework: A phenomenon where a product or service gains additional value as more people use it. Forms include:

Practical Application: Ask whether your offering becomes more valuable with additional users. If yes, prioritize growth strategies and early adoption incentives to reach critical mass.

Real-World Example: Airbnb built different growth strategies for both sides of its marketplace – offering professional photography for hosts to attract guests, while making the booking process seamless for travelers to attract more listings.

The Framework: This model explains how per-unit costs decrease as production volume increases, typically through:

Practical Application: Map your cost structure to identify scaling opportunities. Understand at what volumes significant cost advantages emerge and build growth strategies accordingly.

Real-World Example: Amazon's fulfillment center expansion demonstrates economies of scale in action – with each new facility improving delivery times while reducing per-package shipping costs across their distribution network.

The Framework: This concept, popularized by Warren Buffett, emphasizes operating within domains you genuinely understand. It consists of:

Practical Application: Create a visual map of your personal and organizational competencies. Be ruthlessly honest about where true expertise exists versus where you have merely surface knowledge.

Real-World Example: Berkshire Hathaway's investment success stems directly from this principle – Buffett famously avoided tech investments for decades because they fell outside his circle of competence, only investing in Apple after developing sufficient understanding.

The Framework: This approach favors rapid experimentation over extensive planning through:

Practical Application: Before fully investing in any initiative, define the smallest experiment that could validate your core assumptions. Follow the Build → Measure → Learn cycle rigorously.

Real-World Example: Dropbox founder Drew Houston initially validated his concept not with a working product but with a simple video demonstrating the intended functionality – generating thousands of signups that confirmed market demand before building the actual service.

The Framework: This model examines strategic interactions between rational decision-makers, distinguishing between:

Practical Application: Before negotiating or forming partnerships, map out the incentives of all stakeholders. Look for win-win structures that align interests and create sustainable relationships.

Real-World Example: Intel and Microsoft's "Wintel" partnership demonstrates positive-sum game theory – each company benefited from the other's success, creating aligned incentives that dominated the PC era.

The Framework: This approach flips problem-solving by focusing on avoiding failure rather than seeking success:

Practical Application: Before launching any significant initiative, conduct a pre-mortem. Have team members anonymously write scenarios detailing how the project failed, then address these potential failure points proactively.

Real-World Example: Amazon's leadership often starts with the press release when developing new products – beginning with the end customer experience and working backward, identifying potential disappointments or failures before they happen.

The Framework: These systems show how outputs affect inputs in continuing cycles:

Practical Application: Map the feedback loops in your business operations, customer acquisition, and product development. Identify where positive loops can be strengthened for growth and where negative loops are needed for stability.

Real-World Example: Salesforce's customer success model demonstrates intentional feedback loop design – customer success drives renewals and references, which drive new sales, which fund more customer success resources, creating a virtuous cycle.

True competitive advantage comes when mental models become embedded in organizational culture. Consider these implementation strategies:

The most powerful thinking emerges when you apply multiple models to the same situation. This "model stacking" creates cognitive depth and reveals insights invisible through any single framework.

Try this exercise: Select a current strategic challenge. Analyze it sequentially using three different mental models. Note how each perspective reveals different aspects of the situation and suggests different potential solutions.

Mental models aren't academic concepts – they're practical tools that become more valuable with consistent application. Start with these steps:

Remember, the goal isn't collection but application. A few well-understood mental models consistently applied will transform your decision quality more than dozens superficially grasped.

Before closing this article, try this exercise:

Think about a significant business decision you made in the past six months. Select three mental models from this guide and retrospectively analyze that decision through each lens. What new insights emerge? How might your decision have changed with these frameworks actively in mind?

The quality of your future depends on the quality of your thinking today. These mental models are your path to clearer, more strategic business leadership.

We live in a world flooded with information and noise. Every day, we’re bombarded with data, opinions, and explanations - some insightful, many misleading. In this fog of complexity, how do we make sound judgments? How do we tell what matters from what distracts?

Two mental shortcuts - or heuristics - offer surprisingly effective answers: Occam’s Razor and Hanlon’s Razor.

These aren’t rules of logic or mathematical formulas. They’re guiding principles that help us simplify decisions, explanations, and judgments. Occam helps us cut through complexity. Hanlon helps us judge intent more wisely. Together, they offer a practical compass for clearer thinking.

This article will unpack both razors - what they mean, when to use them, and how they can sharpen your analytical thinking in daily life, leadership, and problem-solving.

This phrase originates from 14th-century logician William of Ockham. At its core, Occam’s Razor urges us to favour simpler explanations that rely on fewer assumptions.

Occam’s Razor doesn’t say the simpler explanation is always right - but it is usually the best starting point. It reminds us not to invent complex theories when a basic one fits.

If two competing explanations explain the same phenomenon, choose the one that makes the fewest assumptions. That’s it.

Reflection Prompt: Next time you're overwhelmed with theories, ask yourself: "Am I adding assumptions that aren't needed?"

Occam’s Razor is a tool, not a verdict. It’s possible to oversimplify and miss crucial variables. For example, attributing a system outage to a single line of code might ignore broader infrastructure issues.

This razor speaks to our tendency to assume ill intent, especially when things go wrong. Hanlon’s Razor reminds us: sometimes people just mess up.

Humans are storytelling creatures. When a colleague misses a deadline or a friend forgets your birthday, it’s easy to assume hostility or disrespect. But often, the truth is simpler: they were overwhelmed, distracted, or just... human.

Micro-Exercise: Think about a recent time you assumed someone wronged you. Could it have been neglect, not malice?

Sometimes, people are malicious. If repeated behaviour, power plays, or manipulation patterns appear - don’t excuse them under the banner of incompetence. Hanlon’s Razor helps as a first lens, not a final judgment.

Both razors push you toward explanations that require fewer assumptions. One focuses on systems and logic; the other on human intent.

Use Occam’s Razor when evaluating technical issues, hypotheses, or process failures.

Use Hanlon’s Razor when interpreting people’s actions, motivations, or communication breakdowns.

Together, they cut through noise and ego.

Before diving into elaborate root cause analyses or crafting complex narratives, apply these razors to test:

These tools guide initial hypothesis formation, not full conclusions. Use them early - then verify with data.

Both heuristics rely on judgment. They work best when paired with experience, pattern recognition, and critical thinking. Avoid using them as intellectual shortcuts or excuses.

Together, they offer a powerful lens for cutting through confusion, especially in high-stakes decisions or emotionally charged situations.

Like any sharp tool, these razors work best in skilled hands. Use them to develop mental discipline, avoid reactive storytelling, and stay grounded in reality.

Lead with simplicity. Judge with clarity.

Because not everything needs a conspiracy theory - and not every mistake needs a villain.

Ever caught yourself reacting to a situation only to think later, “I should’ve thought this through better”? That gap between instinct and insight - that’s where mental models come in.

They’re not rules. They’re not hacks. They’re lenses. Lenses that help you see the world clearly, frame problems better, and choose wisely.

And while blogs, videos, and podcasts can introduce these models, books? Books go deeper. They let you sit with a thinker’s mind for hundreds of pages. They slow you down to speed up your understanding. If you're serious about reshaping how you make decisions, solve problems, or just navigate life more thoughtfully, a good bookshelf beats a thousand browser tabs.

Let’s unpack this.

Mental models are tools for better thinking - but you can’t master tools with summaries. You need context. Application. Contradiction. Depth.

Books give you that. They take a single concept and stretch it out. They show it from different angles, in different domains. They offer stories, studies, frameworks. They argue with themselves. That’s how you learn - by walking around an idea, not just glancing at it.

Think of reading books on mental models like strength training for your brain. Short-form content gives you the warm-up. Books build the muscle.

For this 2025 update, I’ve selected books based on:

This post is organized into five core recommendations (plus a few extras), followed by reading strategies and links to deepen your practice.

Let’s get to the list.

A Nobel-winning psychologist walks us through how our minds work - and fail. System 1 is fast, intuitive, and prone to error. System 2 is slower, more deliberate, but often lazy. This book dives deep into heuristics, biases, and the surprising irrationality of human behavior.

Anyone who makes decisions - so, everyone. But especially useful for product leaders, investors, marketers, and analysts.

This is a collection of speeches and thoughts from Charlie Munger, the lesser-known but equally wise partner of Warren Buffett. It introduces the idea of a “latticework of mental models” and emphasizes multidisciplinary thinking.

People who want to see mental models in action - not just definitions but decision-making playbooks. Also, anyone who prefers wit with their wisdom.

A user-friendly guide with short, crisp explanations of over 300 mental models. Think of it as a curated library you can dip into when you face a problem and wonder, “What model fits here?”

Beginners. Or anyone who wants a reference-style book with real-world examples from tech, economics, and strategy.

A beautiful, multi-volume series that breaks down timeless models across general thinking, physics, chemistry, biology, and more. Each model is explained through narrative, history, and practical use.

Varies by volume, but includes:

Those who prefer deep learning over quick fixes. Also great for anyone who wants to connect models across disciplines.

A billionaire investor lays out his rules for life and work, rooted in radical transparency, feedback loops, and thoughtful decision-making. It’s part philosophy, part playbook, and all conviction.

Founders, executives, team leads - especially those building systems and cultures. Also recommended for people who prefer lists, flowcharts, and frameworks to prose.

Reading is one part. Applying is another. Here’s how to bridge the two.

These books won’t just help you “think better.” They’ll help you see differently. And when you see differently, you act differently.

In a world that rewards clarity, agility, and insight, building your latticework of mental models might be the most valuable investment you make this year.

Have you ever found yourself making the same mistakes, again and again - despite knowing better?

Maybe it’s second-guessing your hiring decisions. Or jumping into a business idea that looked promising… until it didn’t. Or trusting your gut only to realize your gut was echoing your last bias, not your best thinking.

You're not alone. But here's the truth: the best thinkers don’t necessarily think harder. They think in models.

And not just one model. They build a latticework - a mental structure of multiple models from various disciplines that they can apply across contexts. Charlie Munger, the longtime business partner of Warren Buffett, famously attributes his clarity and success to this approach.

So how do you build one for yourself?

Let’s break this down into a practical, step-by-step journey.

Charlie Munger didn’t just invest in companies - he invested in ideas. His approach? “You’ve got to have models in your head,” he said. “And you've got to array your experience - both vicarious and direct - on this latticework of models.”

Think of your brain like a workshop. Every mental model is a tool. Relying on one or two tools (say, your gut instinct or industry experience) might get you by. But to build lasting insight - and avoid costly errors - you need a full toolkit, sharpened and ready.

Individual models can solve individual problems. But complex, real-world decisions often require more than one perspective. For example:

Individually, each is useful. Together? They help you see around corners.

This is not a theory lesson. It’s a practical guide. You’ll learn:

Let’s begin.

You won't build a latticework by sticking to your comfort zone. Read across psychology, biology, economics, history, physics, design, systems thinking, and more. These disciplines offer models that are timeless, scalable, and surprisingly applicable.

Want to understand incentives? Study behavioral economics.

Want to grasp how feedback loops work? Look at biology or systems theory.

Want to think strategically? Military history has a lot to teach.

Try this today:

Pick one book outside your usual domain. If you’re a product leader, read about evolutionary biology. If you’re a writer, read about game theory.

You’re not reading for trivia. You’re looking for transferable ideas. For example:

Keep asking: “What’s the principle here, and where else might it apply?”

You don’t want to just know the models. You want to own them. This means moving from passive to active learning.

For each model, collect case studies across different fields. For example, take “inversion”:

This cross-context exposure deepens understanding.

Great thinkers cross-pollinate ideas. When two mental models intersect, new insight emerges. For instance:

Seeing these connections helps you reason faster and more accurately.

Try this: Take a real challenge - like launching a new product - and apply at least three different models to examine it:

Each time you face a problem, ask: “Which model(s) can help me here?”

For example:

You don’t need to wait for million-dollar choices. Apply models to:

Practice builds pattern recognition.

Reflection is underrated. Every quarter, ask yourself:

Keep a “mental models journal” to capture insights, examples, and links between ideas.

Some models will become obsolete or misleading in certain contexts. That’s okay. A strong latticework evolves. Just like software, you need to patch and update.

Use recommended books, curated lists, and newsletters to keep your toolkit fresh. You’re never done.

Your brain is not just a sponge. It’s a framework builder. And when you build a latticework of mental models, you create a map that helps you:

Recap:

Your mental toolkit is your edge. Build it with care.

We all have. And it’s not because we’re unintelligent or careless. It’s because we’re human.

A few weeks ago, during a leadership coaching session, a client shared how they promoted an employee based on recent wins - only to realize later that their overall track record was inconsistent. “I think I was swayed by the fresh success,” they admitted. What they experienced is something most decision-makers do, unknowingly: they were caught in a cognitive bias called the availability heuristic.

Let’s unpack this together. Because the truth is, our decisions are not just influenced by facts, but also by the frameworks we carry in our minds. The good news? We can train those frameworks. And one of the best tools we have is a well-chosen set of mental models.

Cognitive biases are systematic patterns of deviation from norm or rationality in judgment. Think of them as mental shortcuts - often useful, sometimes dangerous. They help us make sense of a complex world quickly, but they can also mislead us into seeing patterns that aren’t there or dismissing crucial data.

Some familiar ones?

When left unchecked, these mental blind spots lead to faulty hiring decisions, strategic blunders, poor investments, or even conflicts in teams. Biases don’t just affect business; they affect how we interpret others, how we respond to crises, and how we define success.

But here's the powerful truth: mental models can act as a lens clearer, helping us correct or counteract these biases with structured, deliberate thinking.

Mental models like Inversion or Second-Order Thinking help us step outside the echo chamber of our minds. They challenge us to ask, “What if the opposite were true?” or “What happens next?”

Daniel Kahneman describes two systems of thought: fast and intuitive (System 1) vs. slow and deliberate (System 2). Mental models activate System 2. They force a pause. A moment to question. A chance to think better.

Frameworks like First Principles Thinking or Circle of Competence ask us to examine the foundations of our beliefs. Are we assuming something is true just because others do? Are we operating within our area of strength?

Let’s look at six cognitive biases that most professionals fall into - and the mental models that can help us mitigate them:

The Bias: You favor information that confirms your existing beliefs.

Mental Models to Apply:

🛠 Try this: In your next team review, make it a practice to seek at least two disconfirming points before making a final call.

The Bias: Your decisions are unduly influenced by the first piece of information you receive.

Mental Models to Apply:

🛠 Try this: Before setting a sales target or price, do a “clean slate” exercise - what would you recommend if no benchmarks existed?

The Bias: You judge something as more likely based on how easily examples come to mind.

Mental Models to Apply:

🛠 Try this: Keep a bias checklist during big decisions. Include a step to explicitly look for base rate data.

The Bias: You stick with a bad decision because you’ve already invested in it.

Mental Models to Apply:

🛠 Try this: In quarterly reviews, ask: “What would we stop doing if we started from scratch?”

The Bias: You overestimate your competence in areas where you lack experience.

Mental Models to Apply:

🛠 Try this: Before making a big call, map out your “confidence vs. competence” in the area.

The Bias: You focus on winners and forget the failed attempts.

Mental Models to Apply:

🛠 Try this: When studying success stories, research at least one failed attempt in the same space.

So how do we build a culture - both internally and within teams - that helps reduce these biases?

Start by naming your common biases. Are you prone to overconfidence? Are you too quick to decide? Knowing your patterns is the first step to interrupting them.

Reflection Exercise:

Think about a decision in the last 30 days that didn’t go as planned. Which bias may have influenced it?

Just like a pilot has a pre-flight checklist, decision-makers need their own. Before key meetings or decisions, walk through 3-5 mental models that apply.

Sample Questions:

Bias thrives in homogeneity. Disagreement and debate, when healthy, are powerful tools for better decisions. Create room for dissent.

Try This:

In your next meeting, assign roles: The Optimist, The Skeptic, The Data Guardian. Rotate these roles weekly.

Cognitive biases are part of being human. But so is the ability to grow, adapt, and improve our thinking. Mental models offer us not just tools, but mirrors - ways to observe and refine how we think.

When we integrate these models into daily work, our leadership becomes less reactive and more reflective. We stop just making decisions, and start making better ones.

Pick a recent decision you made - big or small.

Ask yourself:

You might be surprised at what you find.

Have you ever explained something to someone and felt like you were talking to a wall?

You crafted your words carefully. You even raised your voice a little. But the message just didn’t land.

That’s the moment most communicators pause and ask: “Was it me? Or were they just not listening?”

Let’s take a different approach. What if it’s not just about what you say, but how you think before you speak?

Let’s unpack that.

In this post, we’ll explore how mental models – the thinking tools that shape how we interpret the world – can make our communication clearer, our persuasion stronger, and our ideas more relatable. Whether you’re leading a team, writing an email, pitching a client, or teaching a concept, these models can help you become not just a better speaker or writer, but a sharper thinker.

We all face similar hurdles:

These challenges aren't just tactical. They’re cognitive. And that’s why mental models can help.

Let's revisit what mental models are. Mental models are frameworks we use to understand how the world works. They’re shortcuts for thinking, but the good kind - the ones that make our decisions more intentional, not automatic.

In communication, the right model can help you:

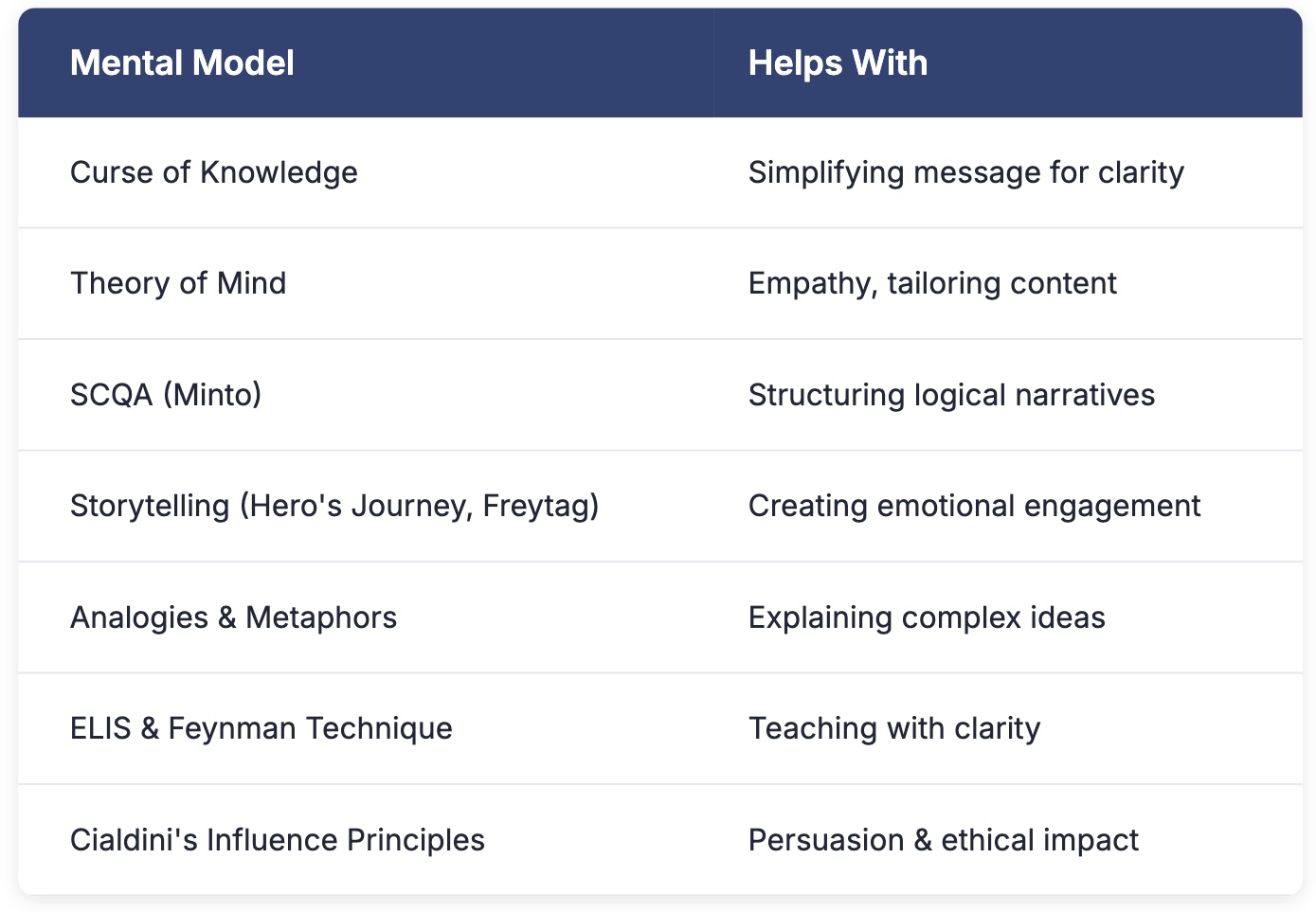

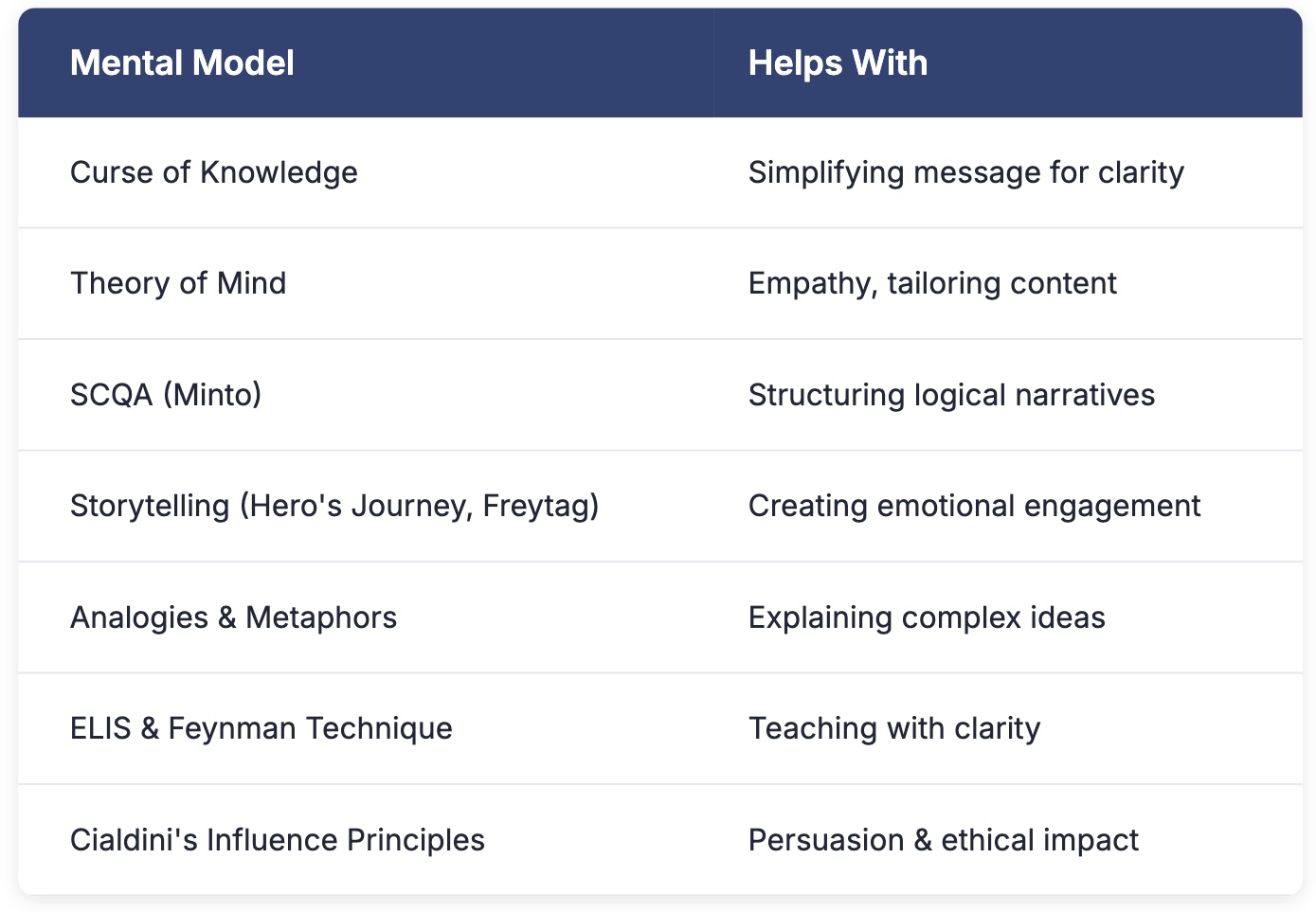

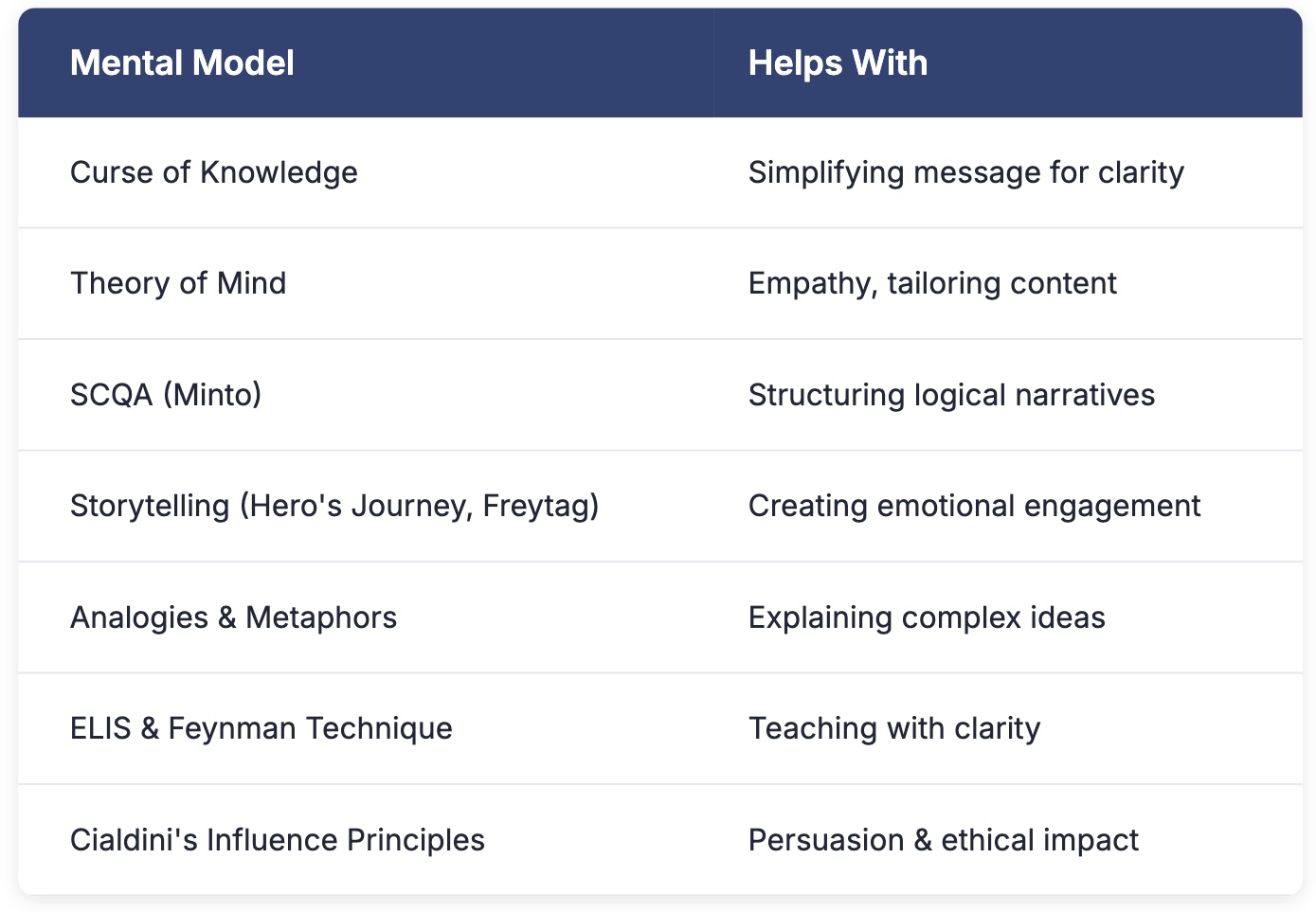

Let’s walk through specific models you can start using today.

The trap: Once you know something well, it’s hard to imagine what it’s like not to know it.

Why it matters: You skip steps. You assume familiarity. You confuse your audience.

What to do: Use tools like empathy mapping or audience avatars. Ask: What does my audience know, believe, fear, and want right now?

Try this: Before you present, write down three things your audience doesn’t know that you take for granted. Then build those into your message.

The principle: Good communicators mentally simulate what others might be thinking.

Why it matters: Anticipating objections, confusion, or emotional reactions makes your message land better.

Application: In sales, this might look like proactively addressing a buyer’s skepticism. In teaching, it means breaking a concept down before students get overwhelmed.

Ask yourself: If I were them, what would I need to feel confident about this idea?

Structure: Situation → Complication → Question → Answer

Why it works: It mirrors the natural flow of attention. You set the context, introduce tension, then provide resolution.

Example:

“Our onboarding time has doubled in the last six months (Situation). This is delaying client outcomes and increasing churn (Complication). How can we speed up onboarding without sacrificing quality? (Question) We propose a revised three-step onboarding framework that reduces setup time by 40% (Answer).”

Use this for: Presentations, memos, reports, even Slack messages.

Why stories work: They engage emotion, attention, and memory.

Application: Whether you’re pitching a product or teaching a principle, wrap it in a narrative. People remember stories, not stats.

Freytag’s Pyramid: Exposition → Rising Action → Climax → Falling Action → Resolution

Try this: Instead of telling people your product saves time, share a customer story that shows it in action.

Why they work: They link unfamiliar concepts to known experiences.

Example:

Use this: In technical pitches, teaching, marketing copy, product demos.

The rule: If you can’t explain it simply, you don’t understand it well enough.

Application:

Test: Could your explanation survive in a conversation with a smart 5-year-old?

Bonus tip: Use the Feynman Technique – write it out in your own words as if teaching it to someone without background knowledge.

These are behavioral models, not just marketing tricks.

Use with care: Influence is not manipulation. The goal is alignment, not coercion.

Example: If you’re presenting a new initiative, show how peers are already using it (social proof) and align it with the team’s values (consistency).

Let’s bring it all together.

Well, we've covered a lot of ground together, haven't we? From understanding what mental models are – those incredible tools for your cognitive toolbox – to exploring some of the most impactful ones, it's been quite the exploration into the architecture of our thoughts. If you remember Priya from our introduction, who went from feeling overwhelmed in her startup to navigating challenges with newfound confidence, it wasn't about suddenly becoming a different person. It was about consciously adopting and using these frameworks to reshape her thinking.

And that's the real heart of it: learning about mental models is the first exciting step, but the true transformation comes from weaving them into your everyday life. Think of it less like a course you complete, and more like developing a new, empowering habit. It’s an ongoing process of noticing, applying, and refining – and every single model you become comfortable with adds a powerful new dimension to how you see the world, make decisions, and solve problems. It won't always be instant, and that's perfectly okay! The key is to stay curious and keep practicing. With each application, you'll find yourself approaching situations with more insight, creativity, and confidence.

I remember a client, let's call her Priya. She was brilliant, passionate about her startup, and working incredibly long hours. Yet, she felt perpetually stuck. "I'm drowning in decisions," she told me during one of our early chats, "and I'm terrified of making the wrong move. It feels like I'm just reacting, not really leading." Priya's challenge wasn't a lack of intelligence or effort – far from it. The real issue, as we discovered together, was that she was trying to solve every diverse business problem with the same limited set of thinking tools she'd always used. It was like trying to build an entire house with only a hammer and a nail – incredibly difficult, and some tasks were simply impossible.

What turned things around for Priya? It began when we started exploring the world of mental models.

What are “mental models”? Let's unpack this together.

Your mind is a kind of mental toolbox. Mental models are simply the tools inside it – they are established concepts, frameworks, or ways of looking at the world that help you understand how things work. They're like blueprints for thinking. The more tools you have in your toolbox, and the better you know how and when to use each one – a wrench for this, a level for that, a detailed schematic for complex projects – the more effectively you can tackle any challenge that comes your way. Without them, we often default to just a couple of familiar "go-to" tools, whether they're the right fit for the problem or not.

Now, why should this matter to you? For Priya, learning to use different mental models wasn't just an interesting intellectual exercise. It fundamentally changed how she approached her business. Suddenly, complex decisions became clearer. She could anticipate challenges further down the road, not just react to immediate fires. She found she could solve problems more creatively and efficiently. And here’s the really exciting part: these kinds of results aren't unique to Priya. By consciously building up your own toolkit of mental models, you can:

It might sound like a big undertaking, but like any skill, it starts with learning the first few tools. This guide is designed to walk you through some of the most effective mental models out there, show you how they work in simple terms, and help you start applying them right away. Ready to upgrade your thinking? Let's begin.

Have you ever hit a wall while solving a problem that just wouldn’t budge - no matter how many times you rehashed your approach??

There was a client once struggling with reducing manufacturing costs for a new product line. Their default move? Benchmark against peers. But benchmarking can be a trap. You only end up iterating on what's already been done. What eventually helped them leap forward wasn’t more data - it was a change in thinking.

That shift came through First Principles Thinking.

Let’s unpack this together.

First Principles Thinking isn’t new. Aristotle spoke about it. Physicists use it. And yes, Elon Musk made it famous in business circles.

At its core, it’s about stripping a problem down to its bare essentials - the truths that are indisputable. From there, you build up a solution as if you’re solving it for the very first time, ignoring what’s always been done.

Musk explained it best when asked why batteries were so expensive: instead of accepting market prices, he asked, “What are the raw materials? What do they really cost?” That simple reframing led to cheaper, scalable battery packs for Tesla.

This is the power of First Principles Thinking - it frees you from conventional constraints and opens the door to original solutions.

We often think by analogy. That means borrowing from what’s been done before:

Analogy Thinking:

“All premium apps charge per user, so we’ll do the same.”

But First Principles Thinking flips the script:

First Principles Thinking:

“Why do apps charge per user? What are our actual costs per usage type? Could we charge by value delivered instead?”

Here’s what happens when you shift from analogy to fundamentals:

Applying First Principles Thinking doesn't require genius. It requires discipline. Here’s a practical process:

Precision matters. Get specific.

Try this:

Write the problem as a question:

“How might we reduce onboarding time for new hires by 50% without sacrificing training quality?”

Break it down like an engineer dismantling a machine.

Let’s say the problem is reducing building costs. You might ask:

This helps distinguish the must-haves from the assumed-to-haves.

Ask why, five times if needed. Push past norms.

Example:

This step is uncomfortable. Good. That means you’re getting somewhere.

Start assembling possibilities using only the truths uncovered in Step 2.

Ask:

This is where innovation takes root. This is where “we’ve always done it this way” finally loses its grip.

Rather than accepting that rockets are expensive, Musk asked:

“What are the raw materials in a rocket, and what do they actually cost?”

His answer: The parts cost far less than the final product. So he built from scratch.

Instead of “Save more this year,” break it down:

This simple reframe often reveals where meaningful cuts (or investments) can be made.

And perhaps most critically: it cultivates clarity. Leaders today don’t just need more answers - they need better questions. First Principles Thinking sharpens both.

In a world obsessed with best practices and competitor checklists, First Principles Thinking pulls us back to what matters: truth, clarity, and creativity. It reminds us that leadership isn’t about doing more - it’s about thinking better.

So, the next time you’re tempted to “see what others are doing,” pause.

Ask instead:

What do I know to be /absolutely true?

And build from there.

Try this today: Pick one decision on your plate. Break it down using Step 2 of this framework. Go deeper than what’s comfortable.

You might just find your breakthrough.

Have you ever solved a problem, only to discover that the solution created three new ones?

You’re not alone. It’s a familiar pattern in decision-making – we act, we fix, we move on. But sometimes, what we fix comes undone. Or worse, it pushes the problem further down the road.

That’s where second-order thinking comes in. A powerful mental model, it urges us to pause, reflect, and ask: “And then what?”

Let’s explore how moving beyond immediate consequences can lead to wiser, longer-lasting decisions.

First-order thinking is seductive. It's fast, it feels satisfying, and it solves something now. But as we’ve seen in everything from quick-fix diets to corporate cost cuts, what looks like a solution today can create ripple effects tomorrow.

The real thinkers – leaders, strategists, and changemakers – aren’t just solving today’s problems. They’re building tomorrow’s realities.

In this blog, let’s unpack the difference between first-order and second-order thinking and learn how to use this powerful lens in business, policy, and personal life.

This is reactive thinking. It focuses on the most obvious and immediate result of a decision.

Example: “Sales are down – let’s lower prices.”

It may feel logical, but it doesn’t ask deeper questions like: Will this attract the right customers? What happens to profit margins? How will competitors respond?

This is layered thinking. It explores not just the immediate effects, but also the consequences of those consequences.

Using the same example: “If we lower prices, will that start a price war? Will we attract bargain hunters instead of loyal customers? Will our brand get diluted?”

Second-order thinking doesn’t eliminate risk – it just makes us more conscious of it.

Good intentions don’t always lead to good outcomes. But thoughtful analysis often does.

Let’s break it down:

First-order: “Let’s slash prices to boost sales.”

Second-order: “Will this reduce perceived value? Will competitors retaliate? Will our operations handle increased volume?”

First-order: “Let’s cap ride-sharing prices to protect customers.”

Second-order: “Will fewer drivers be available? Will service quality drop? Will it reduce supply when demand peaks?”

First-order: “I’ll take this higher-paying job.”

Second-order: “Will it compromise my time with family? Will it lead to burnout?”

These layers are what distinguish reaction from strategy.

Sometimes, the danger isn’t in what we do – it’s in what we didn’t think through.

What’s quick and convenient now may snowball into complexity. Many policies, tech rollouts, or even parenting decisions falter here.

When we only look at the immediate path, we often miss the long tail of value – better alternatives that take longer to show up.

Many corporate decisions fail here. Layoffs that save cash instantly, but crush morale. Efficiency drives that kill creativity.

Remember: The problem with easy answers is they often breed harder questions.

What do we gain when we develop this mindset?

You anticipate roadblocks. You plan for contingencies. Your decisions hold up longer.

You don’t just treat symptoms; you address root causes.

You can't predict every outcome, but you can prepare for possibilities.

It’s the mental equivalent of strength training – slow at first, but incredibly rewarding over time.

Don’t stop at the first answer. Go 2–3 layers deep.

Ask: “What could go wrong?” “What would that trigger?”

Not just the best-case or worst-case. Try: “What else might happen that I’m not seeing?”

If I change X, how will it affect Y and Z?

Who are the stakeholders? What incentives are at play?

Reflect on past decisions: What did you miss? What surprised you?

You don’t need to have all the answers – you just need to ask better questions.

If there’s one thing second-order thinking teaches us, it’s this:

Shortcuts can cost more than we think.

We live in a world of urgency. But wisdom rarely shows up at full speed. It emerges when we pause, widen the lens, and think again.

Let’s summarize:

This week, try this:

Before making a decision, ask “What happens next? And then?” Map it out. Even 5 minutes of pause can reveal long-term costs or unexpected opportunities.

"The quality of your thinking determines the quality of your decisions."

As a business leader or entrepreneur, you face countless decisions daily – from the routine to the potentially transformative. Your competitive advantage? It's not just experience or resources – it's how effectively you think. Mental models – powerful frameworks that shape perception and guide reasoning – can dramatically improve your decision-making quality and business outcomes.

This guide explores 10 essential mental models that will elevate your strategic thinking, enhance your leadership capabilities, and sharpen your entrepreneurial instincts.

The most successful leaders aren't necessarily those with the most experience or resources – they're often those who think better. Every business challenge, whether allocating capital, building teams, or launching products, is directly influenced by the quality of your mental processing.

Mental models serve as cognitive tools that help you:

Consider mental models as your decision navigation system – providing reliable orientation regardless of the business terrain you're traversing.

The Framework: This classic model creates a comprehensive situational assessment by examining:

Practical Application: Before your next strategic planning session, have each team member independently complete a SWOT analysis. Compare the results to identify perception gaps and alignment opportunities. This exercise often reveals blind spots and generates valuable strategic insights.

Real-World Example: Netflix's successful pivot from DVD rentals to streaming demonstrated exceptional SWOT awareness – recognizing their strength in content delivery, the opportunity in emerging technology, the weakness of physical distribution costs, and the threat of emerging digital competitors.

The Framework: This model evaluates competitive intensity and market attractiveness through five dimensions:

Practical Application: Use this framework when entering new markets or re-evaluating your position in existing ones. It reveals structural forces that determine long-term profitability potential beyond current competition.

Real-World Example: Apple's ecosystem strategy directly counters all five forces – creating switching costs to reduce buyer power, controlling app distribution to limit supplier power, creating unique experiences to minimize substitution threats, and building technology barriers against new entrants.

The Framework: This principle states that roughly 80% of effects come from 20% of causes. In business contexts:

Practical Application: Conduct an 80/20 analysis of your customer base, product portfolio, or daily activities. Identify and double down on the vital few inputs generating disproportionate outputs.

Real-World Example: Microsoft famously discovered that fixing the top 20% of reported bugs would resolve 80% of system crashes and errors – allowing more efficient resource allocation in software development.

The Framework: A phenomenon where a product or service gains additional value as more people use it. Forms include:

Practical Application: Ask whether your offering becomes more valuable with additional users. If yes, prioritize growth strategies and early adoption incentives to reach critical mass.

Real-World Example: Airbnb built different growth strategies for both sides of its marketplace – offering professional photography for hosts to attract guests, while making the booking process seamless for travelers to attract more listings.

The Framework: This model explains how per-unit costs decrease as production volume increases, typically through:

Practical Application: Map your cost structure to identify scaling opportunities. Understand at what volumes significant cost advantages emerge and build growth strategies accordingly.

Real-World Example: Amazon's fulfillment center expansion demonstrates economies of scale in action – with each new facility improving delivery times while reducing per-package shipping costs across their distribution network.

The Framework: This concept, popularized by Warren Buffett, emphasizes operating within domains you genuinely understand. It consists of:

Practical Application: Create a visual map of your personal and organizational competencies. Be ruthlessly honest about where true expertise exists versus where you have merely surface knowledge.

Real-World Example: Berkshire Hathaway's investment success stems directly from this principle – Buffett famously avoided tech investments for decades because they fell outside his circle of competence, only investing in Apple after developing sufficient understanding.

The Framework: This approach favors rapid experimentation over extensive planning through:

Practical Application: Before fully investing in any initiative, define the smallest experiment that could validate your core assumptions. Follow the Build → Measure → Learn cycle rigorously.

Real-World Example: Dropbox founder Drew Houston initially validated his concept not with a working product but with a simple video demonstrating the intended functionality – generating thousands of signups that confirmed market demand before building the actual service.

The Framework: This model examines strategic interactions between rational decision-makers, distinguishing between:

Practical Application: Before negotiating or forming partnerships, map out the incentives of all stakeholders. Look for win-win structures that align interests and create sustainable relationships.

Real-World Example: Intel and Microsoft's "Wintel" partnership demonstrates positive-sum game theory – each company benefited from the other's success, creating aligned incentives that dominated the PC era.

The Framework: This approach flips problem-solving by focusing on avoiding failure rather than seeking success:

Practical Application: Before launching any significant initiative, conduct a pre-mortem. Have team members anonymously write scenarios detailing how the project failed, then address these potential failure points proactively.

Real-World Example: Amazon's leadership often starts with the press release when developing new products – beginning with the end customer experience and working backward, identifying potential disappointments or failures before they happen.

The Framework: These systems show how outputs affect inputs in continuing cycles:

Practical Application: Map the feedback loops in your business operations, customer acquisition, and product development. Identify where positive loops can be strengthened for growth and where negative loops are needed for stability.

Real-World Example: Salesforce's customer success model demonstrates intentional feedback loop design – customer success drives renewals and references, which drive new sales, which fund more customer success resources, creating a virtuous cycle.

True competitive advantage comes when mental models become embedded in organizational culture. Consider these implementation strategies:

The most powerful thinking emerges when you apply multiple models to the same situation. This "model stacking" creates cognitive depth and reveals insights invisible through any single framework.

Try this exercise: Select a current strategic challenge. Analyze it sequentially using three different mental models. Note how each perspective reveals different aspects of the situation and suggests different potential solutions.

Mental models aren't academic concepts – they're practical tools that become more valuable with consistent application. Start with these steps:

Remember, the goal isn't collection but application. A few well-understood mental models consistently applied will transform your decision quality more than dozens superficially grasped.

Before closing this article, try this exercise:

Think about a significant business decision you made in the past six months. Select three mental models from this guide and retrospectively analyze that decision through each lens. What new insights emerge? How might your decision have changed with these frameworks actively in mind?

The quality of your future depends on the quality of your thinking today. These mental models are your path to clearer, more strategic business leadership.

We live in a world flooded with information and noise. Every day, we’re bombarded with data, opinions, and explanations - some insightful, many misleading. In this fog of complexity, how do we make sound judgments? How do we tell what matters from what distracts?

Two mental shortcuts - or heuristics - offer surprisingly effective answers: Occam’s Razor and Hanlon’s Razor.

These aren’t rules of logic or mathematical formulas. They’re guiding principles that help us simplify decisions, explanations, and judgments. Occam helps us cut through complexity. Hanlon helps us judge intent more wisely. Together, they offer a practical compass for clearer thinking.

This article will unpack both razors - what they mean, when to use them, and how they can sharpen your analytical thinking in daily life, leadership, and problem-solving.

This phrase originates from 14th-century logician William of Ockham. At its core, Occam’s Razor urges us to favour simpler explanations that rely on fewer assumptions.

Occam’s Razor doesn’t say the simpler explanation is always right - but it is usually the best starting point. It reminds us not to invent complex theories when a basic one fits.

If two competing explanations explain the same phenomenon, choose the one that makes the fewest assumptions. That’s it.

Reflection Prompt: Next time you're overwhelmed with theories, ask yourself: "Am I adding assumptions that aren't needed?"

Occam’s Razor is a tool, not a verdict. It’s possible to oversimplify and miss crucial variables. For example, attributing a system outage to a single line of code might ignore broader infrastructure issues.

This razor speaks to our tendency to assume ill intent, especially when things go wrong. Hanlon’s Razor reminds us: sometimes people just mess up.

Humans are storytelling creatures. When a colleague misses a deadline or a friend forgets your birthday, it’s easy to assume hostility or disrespect. But often, the truth is simpler: they were overwhelmed, distracted, or just... human.

Micro-Exercise: Think about a recent time you assumed someone wronged you. Could it have been neglect, not malice?

Sometimes, people are malicious. If repeated behaviour, power plays, or manipulation patterns appear - don’t excuse them under the banner of incompetence. Hanlon’s Razor helps as a first lens, not a final judgment.

Both razors push you toward explanations that require fewer assumptions. One focuses on systems and logic; the other on human intent.

Use Occam’s Razor when evaluating technical issues, hypotheses, or process failures.

Use Hanlon’s Razor when interpreting people’s actions, motivations, or communication breakdowns.

Together, they cut through noise and ego.

Before diving into elaborate root cause analyses or crafting complex narratives, apply these razors to test:

These tools guide initial hypothesis formation, not full conclusions. Use them early - then verify with data.

Both heuristics rely on judgment. They work best when paired with experience, pattern recognition, and critical thinking. Avoid using them as intellectual shortcuts or excuses.

Together, they offer a powerful lens for cutting through confusion, especially in high-stakes decisions or emotionally charged situations.

Like any sharp tool, these razors work best in skilled hands. Use them to develop mental discipline, avoid reactive storytelling, and stay grounded in reality.

Lead with simplicity. Judge with clarity.

Because not everything needs a conspiracy theory - and not every mistake needs a villain.

Ever caught yourself reacting to a situation only to think later, “I should’ve thought this through better”? That gap between instinct and insight - that’s where mental models come in.

They’re not rules. They’re not hacks. They’re lenses. Lenses that help you see the world clearly, frame problems better, and choose wisely.

And while blogs, videos, and podcasts can introduce these models, books? Books go deeper. They let you sit with a thinker’s mind for hundreds of pages. They slow you down to speed up your understanding. If you're serious about reshaping how you make decisions, solve problems, or just navigate life more thoughtfully, a good bookshelf beats a thousand browser tabs.

Let’s unpack this.

Mental models are tools for better thinking - but you can’t master tools with summaries. You need context. Application. Contradiction. Depth.

Books give you that. They take a single concept and stretch it out. They show it from different angles, in different domains. They offer stories, studies, frameworks. They argue with themselves. That’s how you learn - by walking around an idea, not just glancing at it.

Think of reading books on mental models like strength training for your brain. Short-form content gives you the warm-up. Books build the muscle.

For this 2025 update, I’ve selected books based on:

This post is organized into five core recommendations (plus a few extras), followed by reading strategies and links to deepen your practice.

Let’s get to the list.

A Nobel-winning psychologist walks us through how our minds work - and fail. System 1 is fast, intuitive, and prone to error. System 2 is slower, more deliberate, but often lazy. This book dives deep into heuristics, biases, and the surprising irrationality of human behavior.

Anyone who makes decisions - so, everyone. But especially useful for product leaders, investors, marketers, and analysts.

This is a collection of speeches and thoughts from Charlie Munger, the lesser-known but equally wise partner of Warren Buffett. It introduces the idea of a “latticework of mental models” and emphasizes multidisciplinary thinking.

People who want to see mental models in action - not just definitions but decision-making playbooks. Also, anyone who prefers wit with their wisdom.

A user-friendly guide with short, crisp explanations of over 300 mental models. Think of it as a curated library you can dip into when you face a problem and wonder, “What model fits here?”

Beginners. Or anyone who wants a reference-style book with real-world examples from tech, economics, and strategy.

A beautiful, multi-volume series that breaks down timeless models across general thinking, physics, chemistry, biology, and more. Each model is explained through narrative, history, and practical use.

Varies by volume, but includes:

Those who prefer deep learning over quick fixes. Also great for anyone who wants to connect models across disciplines.

A billionaire investor lays out his rules for life and work, rooted in radical transparency, feedback loops, and thoughtful decision-making. It’s part philosophy, part playbook, and all conviction.

Founders, executives, team leads - especially those building systems and cultures. Also recommended for people who prefer lists, flowcharts, and frameworks to prose.

Reading is one part. Applying is another. Here’s how to bridge the two.

These books won’t just help you “think better.” They’ll help you see differently. And when you see differently, you act differently.

In a world that rewards clarity, agility, and insight, building your latticework of mental models might be the most valuable investment you make this year.

Have you ever found yourself making the same mistakes, again and again - despite knowing better?

Maybe it’s second-guessing your hiring decisions. Or jumping into a business idea that looked promising… until it didn’t. Or trusting your gut only to realize your gut was echoing your last bias, not your best thinking.

You're not alone. But here's the truth: the best thinkers don’t necessarily think harder. They think in models.

And not just one model. They build a latticework - a mental structure of multiple models from various disciplines that they can apply across contexts. Charlie Munger, the longtime business partner of Warren Buffett, famously attributes his clarity and success to this approach.

So how do you build one for yourself?

Let’s break this down into a practical, step-by-step journey.

Charlie Munger didn’t just invest in companies - he invested in ideas. His approach? “You’ve got to have models in your head,” he said. “And you've got to array your experience - both vicarious and direct - on this latticework of models.”

Think of your brain like a workshop. Every mental model is a tool. Relying on one or two tools (say, your gut instinct or industry experience) might get you by. But to build lasting insight - and avoid costly errors - you need a full toolkit, sharpened and ready.

Individual models can solve individual problems. But complex, real-world decisions often require more than one perspective. For example:

Individually, each is useful. Together? They help you see around corners.

This is not a theory lesson. It’s a practical guide. You’ll learn:

Let’s begin.

You won't build a latticework by sticking to your comfort zone. Read across psychology, biology, economics, history, physics, design, systems thinking, and more. These disciplines offer models that are timeless, scalable, and surprisingly applicable.

Want to understand incentives? Study behavioral economics.

Want to grasp how feedback loops work? Look at biology or systems theory.

Want to think strategically? Military history has a lot to teach.

Try this today:

Pick one book outside your usual domain. If you’re a product leader, read about evolutionary biology. If you’re a writer, read about game theory.

You’re not reading for trivia. You’re looking for transferable ideas. For example:

Keep asking: “What’s the principle here, and where else might it apply?”

You don’t want to just know the models. You want to own them. This means moving from passive to active learning.

For each model, collect case studies across different fields. For example, take “inversion”:

This cross-context exposure deepens understanding.

Great thinkers cross-pollinate ideas. When two mental models intersect, new insight emerges. For instance:

Seeing these connections helps you reason faster and more accurately.

Try this: Take a real challenge - like launching a new product - and apply at least three different models to examine it:

Each time you face a problem, ask: “Which model(s) can help me here?”

For example:

You don’t need to wait for million-dollar choices. Apply models to:

Practice builds pattern recognition.

Reflection is underrated. Every quarter, ask yourself:

Keep a “mental models journal” to capture insights, examples, and links between ideas.

Some models will become obsolete or misleading in certain contexts. That’s okay. A strong latticework evolves. Just like software, you need to patch and update.

Use recommended books, curated lists, and newsletters to keep your toolkit fresh. You’re never done.

Your brain is not just a sponge. It’s a framework builder. And when you build a latticework of mental models, you create a map that helps you:

Recap:

Your mental toolkit is your edge. Build it with care.

We all have. And it’s not because we’re unintelligent or careless. It’s because we’re human.

A few weeks ago, during a leadership coaching session, a client shared how they promoted an employee based on recent wins - only to realize later that their overall track record was inconsistent. “I think I was swayed by the fresh success,” they admitted. What they experienced is something most decision-makers do, unknowingly: they were caught in a cognitive bias called the availability heuristic.

Let’s unpack this together. Because the truth is, our decisions are not just influenced by facts, but also by the frameworks we carry in our minds. The good news? We can train those frameworks. And one of the best tools we have is a well-chosen set of mental models.

Cognitive biases are systematic patterns of deviation from norm or rationality in judgment. Think of them as mental shortcuts - often useful, sometimes dangerous. They help us make sense of a complex world quickly, but they can also mislead us into seeing patterns that aren’t there or dismissing crucial data.

Some familiar ones?

When left unchecked, these mental blind spots lead to faulty hiring decisions, strategic blunders, poor investments, or even conflicts in teams. Biases don’t just affect business; they affect how we interpret others, how we respond to crises, and how we define success.

But here's the powerful truth: mental models can act as a lens clearer, helping us correct or counteract these biases with structured, deliberate thinking.

Mental models like Inversion or Second-Order Thinking help us step outside the echo chamber of our minds. They challenge us to ask, “What if the opposite were true?” or “What happens next?”

Daniel Kahneman describes two systems of thought: fast and intuitive (System 1) vs. slow and deliberate (System 2). Mental models activate System 2. They force a pause. A moment to question. A chance to think better.

Frameworks like First Principles Thinking or Circle of Competence ask us to examine the foundations of our beliefs. Are we assuming something is true just because others do? Are we operating within our area of strength?

Let’s look at six cognitive biases that most professionals fall into - and the mental models that can help us mitigate them:

The Bias: You favor information that confirms your existing beliefs.

Mental Models to Apply:

🛠 Try this: In your next team review, make it a practice to seek at least two disconfirming points before making a final call.

The Bias: Your decisions are unduly influenced by the first piece of information you receive.

Mental Models to Apply:

🛠 Try this: Before setting a sales target or price, do a “clean slate” exercise - what would you recommend if no benchmarks existed?

The Bias: You judge something as more likely based on how easily examples come to mind.

Mental Models to Apply:

🛠 Try this: Keep a bias checklist during big decisions. Include a step to explicitly look for base rate data.

The Bias: You stick with a bad decision because you’ve already invested in it.

Mental Models to Apply:

🛠 Try this: In quarterly reviews, ask: “What would we stop doing if we started from scratch?”

The Bias: You overestimate your competence in areas where you lack experience.

Mental Models to Apply:

🛠 Try this: Before making a big call, map out your “confidence vs. competence” in the area.

The Bias: You focus on winners and forget the failed attempts.

Mental Models to Apply:

🛠 Try this: When studying success stories, research at least one failed attempt in the same space.

So how do we build a culture - both internally and within teams - that helps reduce these biases?

Start by naming your common biases. Are you prone to overconfidence? Are you too quick to decide? Knowing your patterns is the first step to interrupting them.

Reflection Exercise:

Think about a decision in the last 30 days that didn’t go as planned. Which bias may have influenced it?

Just like a pilot has a pre-flight checklist, decision-makers need their own. Before key meetings or decisions, walk through 3-5 mental models that apply.

Sample Questions:

Bias thrives in homogeneity. Disagreement and debate, when healthy, are powerful tools for better decisions. Create room for dissent.

Try This:

In your next meeting, assign roles: The Optimist, The Skeptic, The Data Guardian. Rotate these roles weekly.

Cognitive biases are part of being human. But so is the ability to grow, adapt, and improve our thinking. Mental models offer us not just tools, but mirrors - ways to observe and refine how we think.

When we integrate these models into daily work, our leadership becomes less reactive and more reflective. We stop just making decisions, and start making better ones.

Pick a recent decision you made - big or small.

Ask yourself:

You might be surprised at what you find.

Have you ever explained something to someone and felt like you were talking to a wall?

You crafted your words carefully. You even raised your voice a little. But the message just didn’t land.

That’s the moment most communicators pause and ask: “Was it me? Or were they just not listening?”

Let’s take a different approach. What if it’s not just about what you say, but how you think before you speak?

Let’s unpack that.

In this post, we’ll explore how mental models – the thinking tools that shape how we interpret the world – can make our communication clearer, our persuasion stronger, and our ideas more relatable. Whether you’re leading a team, writing an email, pitching a client, or teaching a concept, these models can help you become not just a better speaker or writer, but a sharper thinker.

We all face similar hurdles:

These challenges aren't just tactical. They’re cognitive. And that’s why mental models can help.

Let's revisit what mental models are. Mental models are frameworks we use to understand how the world works. They’re shortcuts for thinking, but the good kind - the ones that make our decisions more intentional, not automatic.

In communication, the right model can help you:

Let’s walk through specific models you can start using today.

The trap: Once you know something well, it’s hard to imagine what it’s like not to know it.

Why it matters: You skip steps. You assume familiarity. You confuse your audience.

What to do: Use tools like empathy mapping or audience avatars. Ask: What does my audience know, believe, fear, and want right now?

Try this: Before you present, write down three things your audience doesn’t know that you take for granted. Then build those into your message.

The principle: Good communicators mentally simulate what others might be thinking.

Why it matters: Anticipating objections, confusion, or emotional reactions makes your message land better.

Application: In sales, this might look like proactively addressing a buyer’s skepticism. In teaching, it means breaking a concept down before students get overwhelmed.

Ask yourself: If I were them, what would I need to feel confident about this idea?

Structure: Situation → Complication → Question → Answer

Why it works: It mirrors the natural flow of attention. You set the context, introduce tension, then provide resolution.

Example:

“Our onboarding time has doubled in the last six months (Situation). This is delaying client outcomes and increasing churn (Complication). How can we speed up onboarding without sacrificing quality? (Question) We propose a revised three-step onboarding framework that reduces setup time by 40% (Answer).”

Use this for: Presentations, memos, reports, even Slack messages.

Why stories work: They engage emotion, attention, and memory.

Application: Whether you’re pitching a product or teaching a principle, wrap it in a narrative. People remember stories, not stats.

Freytag’s Pyramid: Exposition → Rising Action → Climax → Falling Action → Resolution

Try this: Instead of telling people your product saves time, share a customer story that shows it in action.

Why they work: They link unfamiliar concepts to known experiences.

Example:

Use this: In technical pitches, teaching, marketing copy, product demos.

The rule: If you can’t explain it simply, you don’t understand it well enough.

Application:

Test: Could your explanation survive in a conversation with a smart 5-year-old?

Bonus tip: Use the Feynman Technique – write it out in your own words as if teaching it to someone without background knowledge.

These are behavioral models, not just marketing tricks.

Use with care: Influence is not manipulation. The goal is alignment, not coercion.

Example: If you’re presenting a new initiative, show how peers are already using it (social proof) and align it with the team’s values (consistency).

Let’s bring it all together.